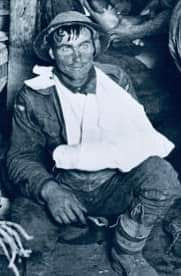

‘Shell Shock’

Captain John Harris was completely exhausted when he collapsed on 24 July 1916. At Pozières, his battalion had suffered under one of the heaviest bombardments of the war. Harris recalled seeing descending shells in their last 40 feet of flight. ‘The only thing to do was grin and bear it.’

Harris later collapsed and was evacuated from the front line.

He had suffered severe shell shock.

In 1917, Harris returned to his battalion, but his ‘nerves’ gave way again at Polygon Wood. When shells exploded close by, Harris fell to the ground, shaking uncontrollably.

A medical officer remembered Harris as suffering from tremor of the hands. He ‘only answered questions slowly and after some delay’. His commanding officer found him to be imbecilic; all he could say was that he was ‘feeling stupid’.

Harris had suffered shell shock for a second time.

Upon returning to Australia Harris found it difficult to ease back into civilian life. His medical files indicate that he never sought treatment for shell shock.

Harris felt embarrassed by his inexplicable ‘bouts of nerves’. His heart often thumped against his chest for apparently no reason. The slamming of a door or the back firing of a car startled him.

Harris didn’t talk much about the war. Yet, the lasting effect of the ‘tremendous bombardment’ upon him was revealed in a letter he sent to historian Charles Bean: he explained that his recollections of Pozières were very ‘vague and shadowy’ owing to ‘shellshock’. ‘I lost my memory in regard to numerous things which happened, of which I was informed afterwards by others.’

Harris taught in schools throughout Australia until 1951. He then applied for a pension, claiming that he suffered from arthritis due to exposure at Ypres in 1917.

He wrote that he found it difficult to get and retain a decent position, as headmasters did not want to employ a cripple. His claim was approved. His health declined in later years.

Confined to a bed, he died in 1960.

The war spawned thousands of John Harrises, who silently bore their terrible burden. For them, the war never ended.

Post-traumatic stress disorder was not recognised as a war-induced ailment until the 1980s.

Like my posts? Take a sneak preview or pre-order ‘Night in Passchendaele’ (out in August 2023)

https://www.panmacmillan.com.au/9781761265976/night-in-passchendaele/

Check out: Scottbennettwriter.com

Photo credit: Australian War Memorial

Comments

Post a Comment